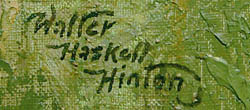

Walter Haskell Hinton (1886-1980)

Homepage

![]()

Early life

Walter Haskell Hinton was born August 24th, 1886 in San Francisco. His father Walter Otho Hinton was a well-traveled man, a linguist with an extraordinary memory who worked for the San Francisco Chronicle, possibly as a compositor. His mother, Mary Washburn Haskell Hinton, had strong artistic abilities. Hinton credited his own excellent visual memory to a combination of his parents’ talents. The family moved to Denver and then to Chicago at the time of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. As a youth he saw a production of Buffalo Bill's Congress of Rough Riders of the World show – probably the one installed adjacent to the Exposition – which nourished his love of the Western pioneer and Native American cultures.

Education

In Chicago, the school system noted Hinton's irrepressible urge to draw and suggested art study. His father had him study under the French artist Albert François Fleury, who took him on landscape painting expeditions. After about a year and a half, Fleury recommended a more formal education, and Hinton attended the Chicago Art Institute starting in 1900. His first intention was to become a fine artist but he enjoyed his illustration classes, and soon wished to study with the great master of fiction illustration, Howard Pyle. But when his father unexpectedly died in 1905, Hinton had to cease fulltime education and take up commercial art in order to provide for his mother and himself. He never did return to formal training after 1907, but he believed learning was a life-long process, and so he read books voraciously to educate himself about the things he painted.

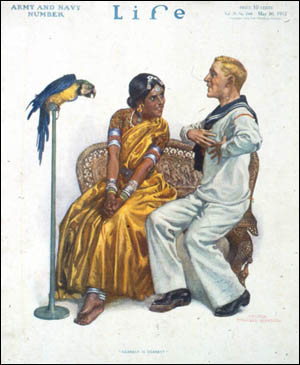

Life before 1930

After his first job in a Chicago engraving house, Hinton was recruited to Milwaukee, first with Hall and Taylor, and then with Cramer-Krasselt, where he remained for several years. There, he became so useful in originating advertising concepts that they sorely missed him when he went traveling in Mexico in 1909. The Mexican Revolution cut his adventures short, and so he returned to Cramer-Kasselt in 1910 and remained there until 1912, when he decided to try his luck in commercial art in New York. There he worked on all kinds of accounts from hosiery to clothing, and he won a cover assignment from Life, which was at that time a prominent humor magazine edited by the eminent illustrator Charles Dana Gibson. But Hinton disliked the city.

He went on to Philadelphia in 1913, where he established a studio at 721 Walnut Street by 1914. He did work for NW Ayers, The Saturday Evening Post, Cheney Silk Co., Atlas Powder, Indian Motorcycles, Liggett & Myers, and Baldwin Locomotive.

In the early Nineteen-Teens, he met and married Marie Stanbridge of Vermont. Sadly, she died in childbirth in 1915, leaving Hinton to raise his son Raymond with his mother Mary’s help. When he was offered a job back in Chicago by the Charles Daniel Frey art studio in 1919, he went, and his mother helped bring up his son there.

In 1921 Hinton became an employee of Barnes & Crosby agency. Throughout the 1920s he worked on accounts such as Allen A. hosiery, Elgin Watch, Westclox, Inland Steel, Successful Farming magazine, and Dairy Farmer magazine. He did well enough that in 1927 he became proud owner of a Cadillac, and in 1928 he could take his mother on a long tour to Alaska via Banff and Washington State. Another extensive trip took him to the Southwest. His travels would contribute to his knowledge of Western and native themes, as he collected artifacts and shot many photographs along the way.

Life after 1930

Economically across the country, the worst year of the Depression was 1933. Hinton had to return to freelancing, as Barnes & Crosby went under. But freelancing suited him, and Hinton was extremely prolific throughout the 1930s, when many other illustrators were going hungry. The field of pulp magazines took off during this decade, and Hinton began doing covers for Western Story, Wild West Weekly, Adventure and Love Story, and other inexpensive titles that people could afford. These paid only modestly, but the illustrations could be done quickly. He also had regular, better-paying cover assignments for Outdoor Life and Sports Afield. In 1937 he was able to buy an unusual, Swiss-chalet-style house in the more rural Glen Ellyn, near Chicago.

It was also in the 1930s and 1940s that he began contributing to four major advertising campaigns that evolved into very long-term relationships.

These were:

-

three series on the history of transportation for Fairmont Railway Motors (now a subsidiary of the Harsco Corporation)

-

a series depicting the use of earth moving machines for Austin-Western

-

a series of calendar and advertising images for John Deere and Co. selling tractors and developing their jumping deer corporate identity

-

a series of scenes from General Washington's life for Washington National Insurance Company

Freelancing also allowed Hinton to paint more non-commissioned work. Over the years he produced many bucolic landscapes, farm scenes, historical images, and pictures of wild animals and native people in majestic wildernesses. These he sold to large printing and publishing firms such as Brown & Bigelow, who distributed them in the form of calendars and art prints; these in turn often made their way into puzzles.

Hinton lived a reasonably comfortable life until his passing in 1980, at age 94. Deere and Co. continues to issue his illustrations in calendars and on merchandise, while collectors of old puzzles, fans of outdoors memorabilia, and vintage farm-equipment aficionados also keep his memory alive.

Personality and Influence

Walter Haskell Hinton was a very independent man. An only child, largely homeschooled and self-taught, and a widower most of his life, he remained self-directed even into his last days. He found raising his son Ray and pursuing his art and his reading quite fulfilling, so he did not join clubs or cultivate many friendships. Nor, it seems, did he even associate with other artists. His house was decorated with carved faces and animals and his yard was kept natural, and so William Slater, who grew up nearby, recalls that some local children regarded his house as spooky!

When they had moved to the neighbourhood in the 1950s, William's parents, Bill and Kitty Slater, thought Hinton rather reclusive and isolated, and so they began to invite him to gatherings. He started to get to know the community better and, as more local people became aware of his work, a few came to commission paintings.

John Higgins-Biddle, who grew up as a neighbor of Hinton’s before the Slaters arrived, does not remember Hinton as either reclusive or mysterious. He writes, “He worked hard and regularly in his yard, his pipe in his teeth or pocket. He was one of the first environmentalists long before the term existed. He was a forceful opponent of the town's spraying to kill mosquitoes, which he claimed also killed the birds. He composted everything and was a valued source of information to our family and others about how to care properly for trees, shrubs, grass, etc. Indeed, in the winter of 1948-49 rabbits ate the bark off a small magnolia tree we had planted to celebrate the birth of our sister. Mr. Hinton advised we wrap the stems carefully with cloth and cover that with foil. If you visit today, you'll see that tree not only survived but is one of the largest, most beautiful magnolias in Glen Ellyn.” Hinton’s appreciation for the environment is especially expressed in his popular calendar paintings, which celebrate native animals and plants so much.

Hinton only seemed reclusive; in fact, when he was socializing, he was an engaging, extroverted speaker who could fascinate his listeners with his encyclopedic knowledge and colorful tales. Self-confident and widely read, he never shied from a sporting argument, and as a man of his times, and proud, he did not easily let go of beliefs that had been with him all his life. He had an impish streak, keeping cheap wine in expensive bottles in his cellar, and dressing up at Halloween for the kids who wended their way past the big bushes and trees to his door.

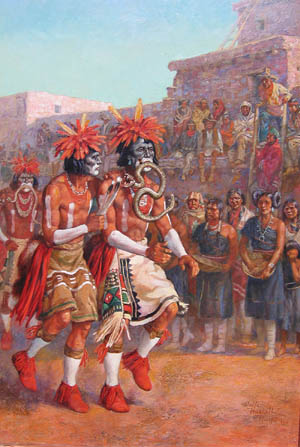

Hinton had the air of a Victorian gentleman, even wearing spats into the 1950s. For a few lucky boys, Hinton was an awesome figure and he had a significant impact on their lives. Kitty Slater remarks that her children's lives were greatly enriched by living next door to the house that everyone inevitably compares to a museum, with this fascinating and erudite man inside. Her son Bill used to visit and watch Hinton paint. In particular, Hinton educated his guests about native culture. Says Bill Slater, "I grew up with Westerns on TV and all that. I didn't know difference between an Apache, a Crow; Mr. Hinton opened me up to the concept that that Indians came from all over, like the Southwest or Alaska, and that they had different cultures. And he was thrilled to be telling you about it. He would point out the differences between costumes and weapons of all the different tribes. My previous idea of Indians was 'circle the wagons' and they shoot everybody."

An army friend of his son Raymond once remarked that Ray revered his father - and those who knew Walter say he cherished his son equally. After Ray left home for the Army Air Corps in 1940, and Walter’s mother died in 1944, Walter’s house was a lot emptier. In 1952, a neighbor, Bill Heald, asked if Hinton would teach his grandson, 6-year-old William Rathje, how to draw and paint. Hinton declined, saying that painters who teach cease to be painters. So Mr. Heald asked if the little boy could come do some yard work on Saturdays, and then as a reward sit and watch Hinton work.

This Hinton heartily agreed to - and over about 10 years, young Bill Rathje gradually developed into a kind of apprentice, although not the traditional kind who would have assisted Hinton on his work. Instead, Bill completed his own drawings and paintings, and Hinton would then - with Bill's permission - touch up them up here and there, to demonstrate an improvement rather than critiquing or questioning Bill's efforts. He says today, "After my immediate family, Mr. Hinton had the most influence in my life." He is especially grateful Hinton never once said a critical word, but let him develop at his own pace in a process of self-directed discovery, always treating him as an equal. Hinton cautioned his protégé not to go into art, because there was no longer any money in it - photography had finally displaced illustrators by about 1960. Instead, Bill's training in drawing benefited him in his studies as an anthropologist. His interest in anthropology was also stimulated by Hinton's collection of non-Western art and his knowledge of other cultures. William Rathje is now a renowned expert on the anthropology of garbage.

Another boy who loved Hinton was the grandson of the man who owned the local shooting range, where Hinton would spend some leisure hours. This boy came to know Hinton well later in life, as he would come by to work on the house. Through visiting and being treated to Hinton's lively lectures about the series of Native American paintings, the boy, by then a man, developed a deep respect for Hinton's art; the works he came to own are among his prized possessions.

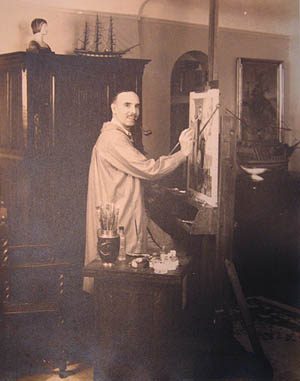

Walter Haskell Hinton as a young man

Students' fancy dress ball, taken in Blackstone Hall, Art Institute of Chicago, about 1904.

Hinton at easel in middle age

Life cover, 1912

Hinton's house in Glen Ellyn, Chicago. Upper window is studio.

Hinton's house in Glen Ellyn, filled with his antiques and artifacts.

Hinton's studio, with specially enlarged North facing window.

Interior architectural feature carved by Hinton.

Hopi Snake Dance, from the series of Native American paintings that hung in Hinton's house and enthralled visitors.

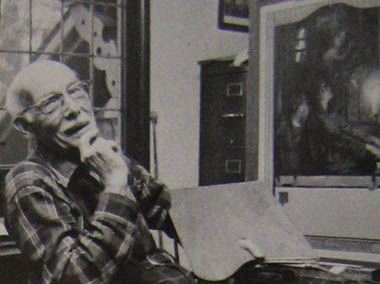

Hinton in 1978, age 92.

Biography

Outdoors magazines

Pulps & Westerns

Farm magazines

John Deere

Fairmont Railways

Washington Nat'l Ins.

Advertising

Native Americans

Calendars & prints

Puzzles